If there is a single living writer who would have spent his Saturday nights with Fitzgerald, Hemingway, and the gang at Lapin Agile, it would be Jay McInerney.

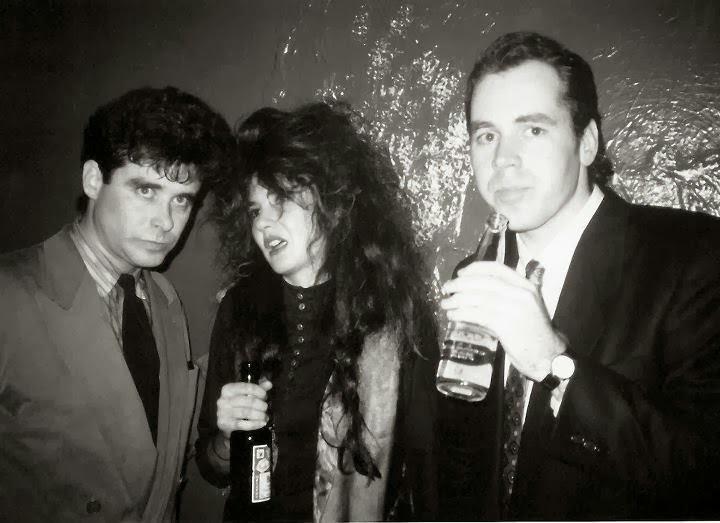

Shooting to literary stardom in the ’80s with his roar of a debut, BRIGHT LIGHTS, BIG CITY, he has since gone on to publish eight novels and a range of short stories chronicling the joys and ignominies of modern life—a sort of Marriage in the City—against the backdrop of 9/11, the financial crisis, and those thrumming lulls in-between. His work is at once a throwback and modern, meticulous and far-reaching. Though he has long outgrown the reputation of Bad Boy Wunderkind, it is still reassuring to know that after a day of writing, as I sit in my pajamas watching This Is Us, McInerney is somewhere out there in the glistening city singlehandedly keeping literary culture alive by asking a stranger to tell his story.

Here, McInerney talks about great expectations, that grand dame—Manhattan– entry into the afterlife, and going whaling.

What do you do to refill the creative well?

Jay McInerney: Travel, fly fish and read.

If you could change one thing about American culture, what would it be?

JM: Does the electoral college count? As a New Yorker I resent the fact that my vote counts far less those of prairie dwellers.

You have described Bright Lights as an “homage to the city I fell in love with.” Is the bloom off the rose or are you still in love with New York? How would you describe Manhattan’s demeanor these days and what is your relationship with her (ex-wife demanding child support payments, spurned lover, ex-girlfriend you can’t remember the name of, best friend, etc.)?

JM: I still love New York and I can’t imagine living anyplace else. I would say it’s more like a best friend at this point than a lover, and yet there’s still a certain buzz I feel when I see the skyline from a plane or from the Long Island Expressway. It would be most accurate to say that it’s different people at different times: best friend, mistress, wife and sometimes, in moments of discovery, exciting stranger. It’s less dirty and dangerous then it was when we first became acquainted, which some people would say is a good thing.

I miss the bad old days but at the same time it’s important not to confuse one’s own aging process with the life cycle of the city. New York in the eighties was New York in my twenties, and it was a glorious time in many ways but it was also an era of rampant crime, two drug epidemics and the AIDs crisis. I have no doubt that those in their twenties are finding new adventures in the city. And I continue to do so. It’s the only place in this country that I know of where one can sit down to dinner with a fashion designer, a rock star, a politician, a writer, an actor, a hedge fund manager and a real estate mogul, as I did a few nights ago.

They say, “You can’t take it with you,” but if you could? What three inanimate objects would you take with you into the afterlife?

JM: My first edition of Tender is the Night inscribed by Fitzgerald to Dorothy Parker. A bottle of 1962 La Tache, in case there are corkscrews in the afterlife. A five weight 9-foot Sage fly rod in case there are trout streams in the afterlife.

If you couldn’t be yourself but a character in a novel, who would you want to be?

JM: I would certainly want to be James Bond in the Ian Fleming novels. I read them all when I was twelve or thirteen.

If you could invent a word, what would it be and what would it mean?

JM: Muniferous. It would be an adjective describing a person large in personality, overflowing and generous in all aspects of life.

Are you on the outside or on the inside?

JM: I think as a writer one has to be both, as Nick Carraway noted in The Great Gatsby. (Not that he was really a writer, but I’m thinking of that passage that goes “I was within and without, simultaneously enchanted and repelled by the inexhaustible variety of life.”) I grew up as an outsider, moving almost every year as a kid, always the new kid in school. And so I worked assiduously throughout my life to get inside, and perhaps in some ways I succeeded. But you never get over that early sense of not belonging.

What are you afraid of?

JM: The four Ds: death, disease, dementia and the Donald.

Living up to literary expectations has been something you’ve talked about openly in interviews. If you could change the fact of your early success, would you? Why or why not, and how have these expectations affected your relationship with your writing?

JM: Early success was gratifying in so many ways that I don’t think I’d want to trade it in. I think many writers give up when their early works aren’t successful and others become somewhat embittered. The success of Bright Lights, Big City cemented my commitment to my profession and ensured that no matter what happened I would always have some kind of audience. On the other hand a slow build to that crescendo might have been gratifying. I hardly knew what to do with that kind of success when it came and it was in many ways overwhelming. I don’t think that it affected my literary development all that much but it certainly affected the reception of my subsequent books, which didn’t necessarily get a fair and unbiased reading in some quarters.

If you had the ear of the entire world for 10 seconds what would you say?

JM: Nationalism and tribalism are diseases.

Does a child have to experience hardship of some kind to grow up and become a great writer?

JM: I suspect that hardship and heartbreak are probably crucial ingredients in the formation of of a great writer. As with vines, stress and acquaintance with adversity build character. A knowledge of suffering seems essential to understanding the human heart.

What do you consider the most critical ingredient for a good marriage?

JM: I’m not sure if I should be considered an authority on marriage since I’ve had four of them. Well, yes, come to think of it, I guess I am an authority. The most important thing seems to be liking each other, which is different than loving each other.

Is your relationship with your published books most akin to:

A. Beloved children

B. Disowned children

C. People you pass on a street who look vaguely familiar, but you keep walking

D. Strangers

E. Other: A few are like beloved children. One or two are like stepchildren, of whom I’m fond. My second novel, Ransom, is like an old college friend whose name and characteristics I can barely remember at this point.

If aliens were to reach Earth a million years from now–the human race long extinct–and they discovered a single book, what do you think they should read?

JM: Ulysses

If you are Ahab, who or what is your Moby Dick?

JM: Donald Trump. Ever since I moved to New York, I’ve wanted to take a harpoon to him.

About Jay McInerney

Jay McInerney is the critically acclaimed author of twelve books – nine of which are works of fiction and the most recent being Bright, Precious Days (2016). Time Magazine cited his first bestselling novel, Bright Lights, Big City (1984), as one of nine generation-defining novels of the twentieth century. Translated into more than 20 languages it has irrefutably achieved the status of a contemporary classic. “Each generation needs its Manhattan novel, and many ache to write it” noted the New York Times Book Review, “but it was McInerney who succeeded”.

His other novels are Ransom (1985), Story of My Life (1988), Brightness Falls (1992), The Last of the Savages (1996), Model Behavior (1999) The Good Life (2006).