“The Mule Confused for a Scorpion”

Welcome to the first lecture for my class, “How to Survive the 21st Century.”

The germinating idea behind this class was to form a forum not just to read great books together, but to investigate whether or not they have any practical bearing on our modern lives – if they can help us live more connectedly and well.

We begin today with Lecture #1, an exploration of Graham Greene’s The Power and the Glory, a bleak, meditative classic about the irrepressible power of faith, humankind, and ideas.

First published in 1940, it was Greene’s 4th novel, described by John Updike as “Greene’s masterpiece… The energy and grandeur of his finest novel derive from the… will toward compassion. …It succeeds resoundingly.”

TIME magazine named it one of the 100 best novels of the 20th Century.

Here, we will explore if The Power and the Glory actually lives up to such a high standard. At first glance – with its overt theme of Catholicism, sacrilege, and sainthoods – it can seem dated. The best novels transcend time and place, granting a universality to the human experience – showing us what it means to be here, now, reminding us of something we knew but have somehow forgotten.

Does The Power and the Glory have such transcendence?

Let’s explore.

I. Graham Greene: The Man, The Myth

Henry Graham Greene was a British novelist, enjoying fame and notoriety for his work and life that spanned nearly a century: 1904 – 1991. He wrote 25 novels, a literary career shifting between film reviews, journalism, serious novels of critical acclaim – such as The Power and the Glory and The Heart of the Matter – where he willfully explored weightier issues of faith, religious persecution – and with so-called entertainments, action-oriented thrillers involving spies, counterintelligence, and manhunts, such as The Third Man. Many of his novels take place in exotic locations, all of which he visited firsthand, from Cuba to Haiti to Vietnam to Africa. During WWII Greene was actually recruited by MI6 and worked as a freelance intelligence officer under the direction of super-spy Kim Philby (later revealed to be one of the worst Russian double-agents in British history) stationed in Sierra Leone.

II. The Germinating Background of ‘The Power and the Glory’

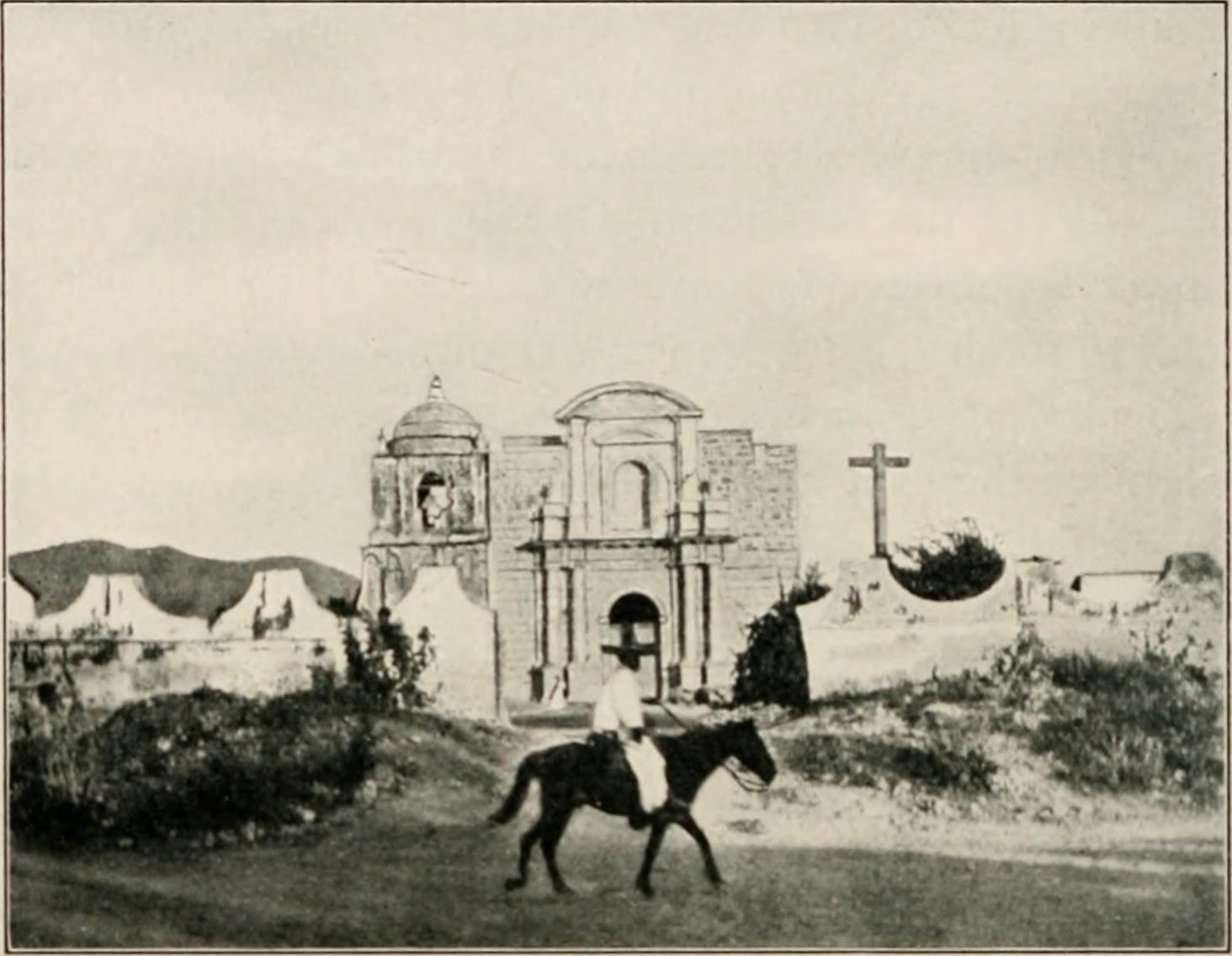

In 1938 Greene was sued by Shirley Temple’s management for libel over a scathing review he wrote of her film Wee Willie Winkie in Night and Day magazine. In the article he contended Temple’s popularity was sexual in nature, implying her fans were dirty old men. In order to escape a convoluted court case, Greene accepted a newspaper assignment in Southern Mexico. It was there in March and April 1938 Greene traveled the Tabasco and Chiapas areas of Mexico documenting firsthand how Catholicism was the subject of an egregious persecution known as the Cristero War. This research became the basis for The Power and the Glory.

III. Mexico in the 1920s and the Persecution of the Catholic Faith

The story takes place during an actual time in Mexican history when in 1926 President Calles outlawed the Catholic church. Persecution was particularly vicious in the state known as Tabasco under the dictatorship of its governor, Tomás Garrido Canabal. It was this man upon whom Graham Greene based the character of the lieutenant in The Power and the Glory.

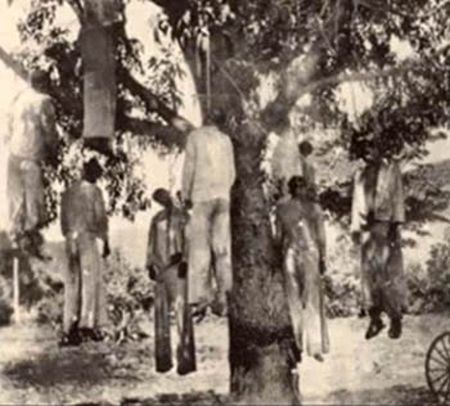

Canabal was a socialist. (He named his son Lenin.) He despised what he had perceived firsthand as the gross corruption and hypocrisy of organized religion, exactly as the lieutenant does in the novel. He witnessed its destruction, its pervasive hold over the lives of the people. He believed the hope for a promised land after death negated the possibility of reality and real life and thus he made it his mission to eradicate Catholicism from public life as if it were a plague.

Canabal, in the course of his rule, was responsible for executing countless priests and sending the remainder into hiding. In contrast to such viciousness, he was a great supporter of women’s rights, granting women the right to vote in Tabasco in 1934 – the second state in Mexico to do so. And so we encounter a living paradox, a real-life person at once dogmatic and vicious, irrational and forward-thinking, and thus unable to be pigeonholed into a stereotype – a type of characterization Greene was drawn to, something to keep in mind in our own times. We will be returning to this point later.

IV. A Post-Apocalyptic Wasteland Straight Out of ‘Mad Max’

From the first images of Chapter 1, we are introduced to a landscape straight out of Mad Max or Cormac McCarthy’s The Road. It is willfully, even absurdly without hope, laughter, or light. The town, locations, and main characters remain unnamed, which only emphasizes the indolent pointlessness of all human life in such a setting. Only the vultures are content.

In the opening pages, Greene systematically crushes everything that we as functioning citizens of the Western World have historically held sacred and good, considered crucial to our wellbeing. Mothers. Memory. Time. Children. Home. One by one, like a long-ranging sniper ticking off Coke cans at 100 yards, Greene renders them all defunct here in this brutal landscape, totally invalid.

The first mention of a mother in the book: “the old sour bitch; she never cared much for me.” Memory – what grounds across time and place, giving our lives context and meaning – is murky and uncertain. Thoughts flit randomly in and out of consciousness. There is no sense of errand or purpose. The pitiable individual who ushers us in and out of the book – Mr. Tench, a dentist – leaves his house to retrieve a can of ether, but almost immediately forgets this task and can’t remember what he’s meant to do.

Time is unaccounted for and undocumented. Throughout the novel there is a marked absence of clocks. “The darkness was always the same and there were no clocks, nothing to indicate time passing. The only punctuation of the night was the sound of urination.”

Home is a defunct concept. Tench describes his home as somewhere else, a dreamlike place he will go back to one day, and later in the book we are told that home is “where there is a chair and a glass” for drinking yourself to death.

Children are absent, lost, and irrelevant. The death of a child is recounted as cursory. Later in the book, a child – a symbol of hope and possibility – is portrayed as an entity moving toward an inevitable state of decay and corruption: “The world was in her heart already, like the small pot of decay in a fruit.”

Mr. Tench has difficulty recalling his own child who died. He can remember the watering can that his children used, the color and how much it cost, but cannot remember his children themselves. “As for the kids,” he says, “I can’t remember much else but them crying.”

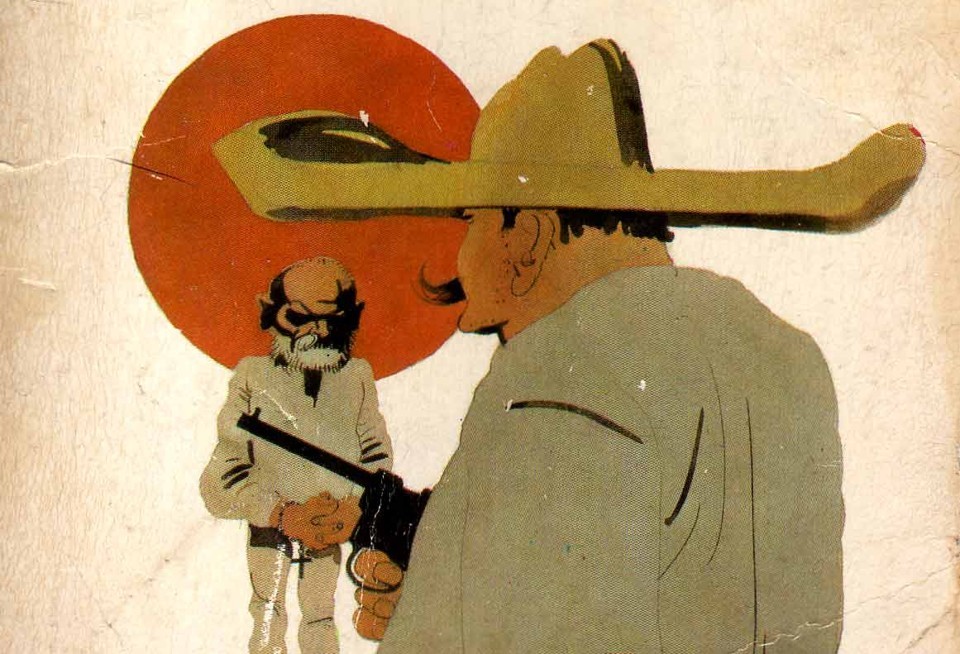

The Priest – the antihero of the book – first appears only incidentally as someone we barely pay attention to, a bookmark, a nameless stranger. He is presented as both pathetic and in a state of paralysis: “The man’s dark suit and sloping shoulders reminded [Tench] uncomfortably of a coffin and death was in his carious mouth already.” Carious means decayed, rotten. He literally has a rotten mouth, Greene’s not so subtle tip-off to the man’s conflict, his corrupted faith in contrast to his actions and thoughts.

“He had the air, in his hollowness and neglect of somebody of no account who had been beaten up incidentally.”

“He sat there like a black question mark, ready to go, ready to stay, poised on the chair.” This is someone literally paralyzed, alive but unable to move or be effective in any way.

This bleak landscape and the lives barely surviving inside it are reminiscent of Macbeth, “tales told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.” Cormac McCarthy’s post-apocalyptic The Road also comes to mind: “All things of grace and beauty such that one holds them to one’s heart, have a commen provenance in pain. Their birth in grief and ashes.”

In other words, out of this grief and ashes, grace and beauty may be born. Greene has boiled down the human experience, stripped it away to its most rudimentary and heartbroken in order to see what is really there underneath it and to investigate what true redemption and salvation might look like in such a world.

V. Getting Born: “He Who is Not Busy Being Born is Busy Dying” – Bob Dylan

Greene pulls us deeper into the novel. We follow the priest through a sequential, Apocalypse-Now-like odyssey veering between his encounters with strangers as he flees deep into the countryside and his often vain attempt to carry out the most meager of rituals and rites of his faith. We hear voices of a range of other characters – mothers, fathers, husbands, wives, old and young. Greene details a breadth of human experience that is wavering, delusional, insecure, revealing the vast gulf between human thoughts and real life, an ideal and reality.

Over the course of the novel we encounter men with throbbing toothaches, recurrent imagery of wild animals (often mistaken for people and vice versa), and most critically of all, an ever-present theme of blindness.

Characters stumble around in the dark, literally and figuratively.

The priest making his way to Carmen in pitch darkness monitors his way forward only by counting in his head: “He began again one, two, three, four, and then a tree. Something moved under his foot and he thought of scorpions.”

That scorpion, as it turns out, is actually a mule. In such a gross miscalculation, Greene highlights the vast gulf that exists inside our minds and the actual reality.

“One, two, three, and suddenly the grotesque cry of a mule came out of the dark; it was hungry.”

Along similar lines, twice the lieutenant encounters his quarry the priest in the course of his journey and twice he lets him go, unable to identify in the real world that which he relentlessly seeks in his mind. Again the scorpion is actually a mule.

During a drinking round, Jefe – the chief of police – also fails to identify the priest. Later, when the priest is brought into the police station and sees his own Wanted poster hanging on the wall the entire station doesn’t recognize him. “He was absorbed in his own portrait. There he sat among the white starched dresses of the first communicants. Somebody had put a ring around his face to pick it out.”

In one of my favorite passages in the novel, the priest is thrown in a pitch dark cell. It’s too dark for him to see the faces of his fellow prisoners. There are only voices. It’s in this blind state that he’s able to not only come to terms with his own failings, but begin a transformation toward legitimate compassion. It’s the first extended scene in the novel of stillness, kindness, a quiet moment, ultimately fleeting yet devoid of despair.

“He couldn’t see her in the darkness, but there were plenty of faces he could remember from the old days which fitted the voice. When you visualized a man or woman carefully, you could always feel pity – that was a quality God’s image carried with it. When you saw the lies at the corners of the eyes, the shape of the mouth, how the hair grew, it was impossible to hate. Hate was just a failure of imagination.”

VI. Sight

When dawn arrives and sight is at last granted, when the lieutenant and the whiskey priest find each other, they sit down and talk, a connection revealing not only the vast differences between them – there is no good or evil here, no obvious superhero and master villain – but a quiet common ground. They agree more than they disagree. Both want to safeguard the future for the next generation – the lieutenant thinking of this in terms of his constituents (“Those men I shot. They were my own people. I wanted to give them the whole world.”), and the priest in the very specific image of his bastard daughter, Brigitta (“It was for her only that he prayed”).

The lieutenant acknowledges the priest isn’t a bad man. Yet, because the lieutenant adheres to a dogmatic desire to convict and condemn the priest, what should be the lieutenant’s moment of triumph, escorting the apprehended priest through town, turns out to be frustrating and unfulfilling.

“A small boy watched them pass, he called out to the lieutenant, ‘Lieutenant, have you got him?’ and the lieutenant dimly remembered the face – one day in the plaza – a broken bottle, and he tried to smile back, an odd sour grimace without triumph or hope.”

Greene illustrates there can be no sense of triumph, because the lieutenant has not actually seen what is in front of him. He still acts according to the rigid tenets of his own mind, an ideal, which leave no room for the reality of human frailty, that there can be a division between the office of Catholicism and faith. Human frailty is separate from the larger, more powerful reality of faith of which it attempts to give voice. In other words, if a sailor tries to describe the ocean to a blind man and fails, that doesn’t mean the sea does not exist. Greene exemplifies the irrepressible nature of faith by having yet another priest arrive at the end of the novel in need of hiding. The individuals may fail. But the power of faith itself will continue on. Greene shows us that the more dogged an adherence to an ideal, the more corrupt and failing the character.

Meanwhile, in contrast to the lieutenant’s lack of growth, the priest has undergone a true transformation. This change is not overt or obvious. It can barely be perceived by others or even himself. Even in the final moments of his life he considers himself as a wretch, a failure. Yet his move toward compassion and an honest vision of the world, compassion for others – as evidenced through his love for his child – is real. And thus he is as close to a saint as we can find in this world.

He selflessly performs last rites on a bandit even though he knows this will lead to his capture and death. Moments before his death, he doesn’t feel the clichéd rush of goodness or the headiness of sacrifice and martyrdom but – and this is one of the most ingenious lines of the book – “like someone who had missed happiness by seconds at an appointed place.”

We witness the priest’s death through old Mr. Tench again, the dentist, as unlofty a witness and bard as they come.

“The crash of the rifles shook Mr. Tench: they seemed to vibrate inside his own guts; he felt sick and shut his eyes. Then there was a single shot, and opening them again he saw the officer stuffing his gun back into his holster, and the little man was a routine heap beside the wall – something unimportant which had to be cleared away.”

And so Greene shows us what sainthood looks like in the real world. It is small, barely perceptible, and it isn’t what we necessarily hold in our minds as an image of “sainthood” and “martyrdom.” But it’s real.

VII. How Can This Help Us Survive the 21st Century?

We are living in a perceived world of polar opposites, agreement and discord, war and peace, liberals and conservatives, Democrats, Republicans, pro-Life, pro-Choice, native, immigrant, accepted, excluded.

Social media and cable news have constructed this antipodal, gladiator arena. They’ve turned our world into a fight between adversaries and allies, villains and heroes. This has nothing to do with the reality of how people actually are. As Greene has shown us, such divisiveness exists first and foremost in our own warped perception. We may all very well be mistaking mules for scorpions.

The Power and the Glory urges us to reconsider such a conflict-ridden construction for our own wellbeing. The lieutenant’s way of condemnation leads only to a sense of frustration. The way of the priest is the better way and thus the book illustrates:

1. Much of the perceived villains, threats, and menaces in our lives exist chiefly within our own minds.

2. The reality of good, evil, saint, sinner, is much more nuanced and difficult to perceive.

3. The true act of compassion requires not an adherence to a dogmatic ideal or label, but a refusal for categorical condemnation in favor of a more quiet, humbled investigation of the self and the real world in order to see what is actually there, and finally…

4. What is actually there could very well be a common ground.

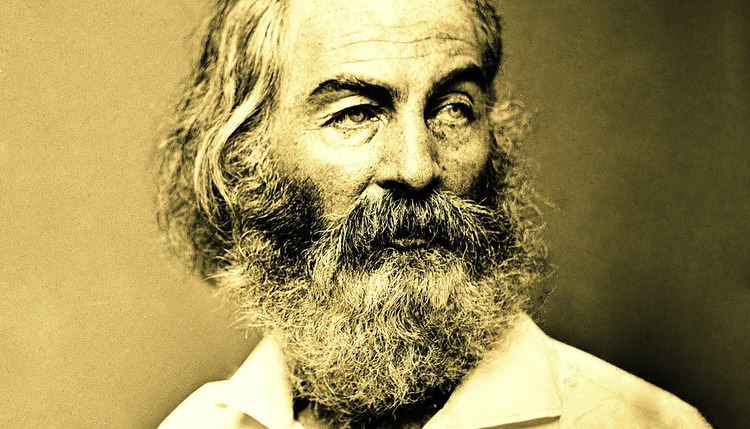

Walt Whitman, observing New York City in 1855 wrote of similar struggles that Greene’s whiskey priest faced – struggles that we all face – in Leaves of Grass:

O ME! O life!… of the questions of these recurring;

Of the endless trains of the faithless – of cities fill’d with the foolish;

Of myself forever reproaching myself, (for who more foolish than I, and who more faithless?)

Of eyes that vainly crave the light – of the objects mean – of the struggle ever renew’d;

Of the poor results of all – of the plodding and sordid crowds I see around me;

Of the empty and useless years of the rest – with the rest me intertwined;

The question, O me! so sad, recurring – What good amid these, O me, O life?Answer.

That you are here – that life exists, and identity;

That the powerful play goes on, and you may contribute a verse.

As Greene shows us, the verse that we contribute might be small and scarcely audible. It might be filled with mistakes and sound strange. But nevertheless in the understanding that we are all struggling simply by being human – at times doing well, at times poorly, at once strong, at once weak – we are afforded a wider, more accurate view of the modern world. And thus a meaningful life can be possible.

So that’s a wrap on Book #1, The Power and the Glory.

I hope it will at the very least cause you not to be so quick to condemn someone or something that suddenly appears in your inbox or Twitter feed or even in the New York Times, making you want to scream or throw something. Instead, maybe, just maybe you’ll hold off on judgment – at least for five minutes – reconsidering your position.

After all, that scorpion might actually be a mule…

Stay tuned in March for my next lecture on Book #2: Neuromancer by William Gibson, whereupon we leave the Mexican countryside and enter a chilly world in the near-future where the sky is the color of the television tuned to a dead channel. Tag all thoughts and questions as you read #readtosurvive and I’ll do my best to cover them all.

Last but not least, I’ll have an update for you shortly on my next book so stay tuned for that.

And happy reading.