Serialized dramas are enjoying a resurgence of late, thanks to the podcast. Some of the first innovators in the space were Joseph Fink and Jeffrey Cranor, the masterminds behind the sci-fi podcast hit Welcome to Night Vale. Taking a page from Orson Welles’ War of the Worlds—with a touch of good old-fashioned BBC radio tossed in for good measure–the podcast unfolds in the format of a community broadcast, detailing the strange conspiracies of a remote desert town.

Since its inception in 2012—predating even the lightning rod of Serial–the podcast has been downloaded over 140 million times and has given rise to a NYT-bestselling novel, a live show, and an imprint called Night Vale Presents. And so an audio empire is born.

I talked with the creators about fandom, spy communications and the Denver airport, Off-Off-Broadway theatre, and the ultimate inexplicable phenomenon—otherwise known as creation.

All great art is an investigation of that which terrifies the author. Given the intensity and complexity of the Night Vale world, what are you both respectively afraid of on a gut-level?

Joseph: We’re both quite afraid of flying. Which is why it’s interesting that we’ve decided to get into careers, between book touring and the touring of our live show, where we fly over 50 times a year. I don’t know whether it helps my writing that I confront mortal terror on a regular basis. Certainly it probably isn’t helping my health.

Jeffrey: Definitely flying. Also spiders. I’m getting better about dealing with both, but at a gut level, I have a hard time facing either. Especially spiders. Have you seen their faces? Awful. Just awful.

I was so delighted to find a kinship in our biographies, that both of you when first moving to New York, pounded the pavement in Off-Off-Broadway East Village theatre before coming together to write as a full-time job. How do you look back on that scrappier time now, and how do your theatre backgrounds inform your writing?

Jeffrey: Working with the New York Neo-Futurists (I was a member of that theater collective, and Joseph volunteered for us, which is how we met), was a fantastic and formative time for me. The aesthetic is about immediacy and honesty, directly communicating with the audience in front of you, rather than pretending some other story as people passively watch. The show the Neos do (Too Much Light Makes the Baby Go Blind) changes weekly and addresses current events on micro and macro levels.

As a writer, I usually relied on words to tell stories, rather than sets or costumes or dance or movement. I couldn’t hide behind flourishing prose, because I had to find ways to speak directly to a room full of people in a way that was heightened and interesting without being dense or writerly. I fell back on poetry quite a bit, as well as performative styles that embraced the intimacy of a tiny, 90-seat theater.

When we started Night Vale, we went with the radio broadcast motif, and there’s a similar intimacy to that – a message broadcast to many but received in a personal, warm way. “I, the host, am speaking directly to you, the listener. It is only us. Here. Now.”

Plus the workload of writing constantly, weekly, prepared me for the rigor of writing 5,000+ words a month for our podcast. That helped a lot.

Joseph: I think the main thing it taught me is the value of just constantly creating new work. Always having a project, and putting everything you have in that project, and then letting it recede into the past so you can get started on the next thing.

I owe almost everything I have to the off-off-Broadway community. It’s how I met my wife, my writing partner, and almost every person I know in New York. I don’t know what my life would have looked like without it, but nothing like what it is now.

Joseph, you have said that Night Vale began as an exploration of conspiracy theories, of which you actually believe almost none. What is the one conspiracy theory that you do believe, or, at the very least, wouldn’t be surprised if it turned out to be true? (Jeffrey, chime in as well.)

Joseph: I think rich and powerful people regularly work to cheat the system in order to stay in power and enrich themselves. I just don’t think it’s done with the kind of elegance and narrative force that most conspiracies ascribe to them. I think rich and powerful people are just as clumsy and greedy and simple in their designs as everyone else. They just have more reach.

That said, one conspiracy theory that is almost certainly real is numbers stations. They are radio stations all over the world playing monotone readings of numbers, interspersed with chimes or simple melodies. They exist in almost every language, and have been around about as long as widespread radio use.

It is commonly understood that they are a communication method for spies. A way for a spy to receive messages by just listening to the radio and then translating the otherwise unbreakable code using a one-time pad. I believe that this is true, because it makes perfect sense.

What is odd is that in over half a century of their existence in almost every country, not a single bit of documentation or proof has surfaced about these radio stations. Their explanation exists only in our assumptions.

Jeffrey: My favorite conspiracy is the Denver airport. It’s a wonderful afternoon of googling, if you’re interested. There’s the idea that it was privately funded, and there’s a sign outside of it crediting the New World Order. It was built far away from the actual city, despite Denver already having a perfectly good airport much closer to town, and during construction, people noticed tents and scaffolding consistent with deep underground structures, not runways and tarmacs. Many believe this is where the Illuminati or lizard people or most likely (as Joseph alludes to above) incredibly wealthy and influential people can go and hide during some armageddon-level incident.

During a particularly close call with a meteor to earth a few years back, President Obama abruptly announced a speaking engagement in Denver. It is believed by some that he did this in order to be close to said bunkers.

But most impressive and terrifying is the artwork. First, there’s the enormous, hideous bucking bronco statue outside as you drive in. The statue literally killed its creator. That’s not a conspiracy. It fell on him. But the details of the horse make it look devilish, something out of Robert Browning’s “Childe Roland”:

Alive? he might be dead for aught I know,

With that red, gaunt and collop’d neck a-strain,

And shut eyes underneath the rusty mane;

Seldom went such grotesqueness with such woe;

I never saw a brute I hated so;

He must be wicked to deserve such pain.

And finally, the murals. Oh lord the murals. Each one depicting an ongoing story of the end of the world and then the rebirth of nations (new world order!). One showed a person in olive drab cloak and gas mask, with an AK-47 in one hand and a scimitar in the other, with which they’re stabbing a dove out of the air. Another showed children crying over dead animals as the forest behind them burns. They were quite astonishing.

Like the numbers stations, the Denver Airport is quite real, but the origins and meaning behind them are probably never to be fully understood.

For all writers there is always some piece of art—a passage in a book, a monologue, a live performance, a sketch, advertisement, photo–that serves as a funny bone, reverberating through you in some bewitching, surprising way, and staying with you, year after year, as a source of inspiration and sense of the unknown. What are yours?

Jeffrey: I think of Will Eno’s play/monologue Thom Pain (based on nothing). Eno plays with narrative expectations in a lovely way, and he is not afraid to be confrontational with his audiences. I always marvel at his ability to set up action and intentions only to undercut them. He builds an arc, and you go with it for a bit, and then suddenly he takes it away. He starts again, likely in a different direction. And rather than the plot being the driving force of the audience’s emotional energy, it is the performance itself. In literature, we want the story to be great. In theater, we want the performer to be great.

There’s a passage in Thom Pain where the narrator tells the audience to imagine a boy. Imagine what he’s wearing (cowboy suit). Imagine his disposition (shy and timid). Imagine again what he’s wearing (it’s still a cowboy suit, but it’s shorts and shoes, no cowboy boots). Imagine he is outside, dreaming. Moments after a passing storm. He has a stick with which he writes things in the mud.

Eno has us then break the boys’ arm or give him an injury of some sort. Make it to where he cannot walk straight. Then to imagine the stick is a violin bow. That the boy is part of a great orchestra, that we are a beat before the performance of a concerto the whole world can hear. We must picture the sky, the birds, the collective breath of all humanity.

Then the monologue abruptly concludes with “Now go fuck yourselves,” and there is a long pause. Picture whatever you want, the narrator says.

Joseph: When I was 22 and had just moved to New York City without knowing a single person in the city, I happened to pick up a book called Vacation by the novelist Deb Olin Unferth. I bought it because it was half off and it had a cool cover.

When I finished reading it, I immediately started over from the beginning. I thought I was already pretty good at writing, but reading it made me realize how much I had to learn. I knew that I needed to learn how to write like that, how to do the kinds of things to the language that Deb Olin Unferth was doing.

One passage always sticks with me. About a quarter of the way into the book, an earthquake happens, and abruptly the story stops and we are in a short essay about how to prepare for an earthquake. It suggests, among other things, that you keep a whistle with you so that you can be found in the rubble. But it also points out that it would be easy to be surprised by an earthquake without the whistle handy. After suggesting and then dismissing a series of possible solutions, the book tells you that the only real way to prepare for an earthquake is to keep the whistle in your mouth at all times, preventing you from doing anything else. It advises you to put your life on hold so that you can be always ready for the earthquake. The essay ends: “Wait for the earthquake. The earthquake is coming.”

At the time, my father was dying, and had been for several years. It was never clear when it would happen, but we all knew it would be soon. That passage about the earthquake expressed for me completely the feeling of being made paralyzed or stagnant in waiting for the horrible thing you know is coming but you don’t know when.

What is your favorite Night Vale character and/or establishment and why?

Joseph: Some characters are just very fun to write. Michelle Nguyen, for instance, with her hipster exterior and deeply sad interior. Or the Faceless Old Woman, whose way of speaking has a certain rhythm and poetry that is a joy to write.

A lot of the fun of writing Night Vale, because we are working with actors, is less about the characters and more about the people playing them. We can write to their abilities, and challenge them with difficult passages. For instance, one of our actors is excellent at impressions, and so I wrote a passage in a live show for him in which he had to rapidly imitate almost every character in our cast.

These kind of challenges aren’t just fun to write, but they make memorable moments for the audience. I think there is nothing more gripping as an audience member than watching a talented performer genuinely struggle to complete a difficult task. And so I seek that out whenever possible, and write toward that struggle for the performer.

One of the things I love so much about the world you created is its clarity of vision. You have both talked about your disciplined approach to universe continuity. How do you keep track of the details and overarching design of the world? What is possible in Night Vale and impossible? Was there ever a moment when you felt you had written yourselves into a corner? How did you get out of it?

Jeffrey: We keep track of universe continuity mostly in our heads. We also use shared folders where we keep all of our scripts, so whenever we’re building on a previously-told story, we can search back through the old episodes & verify the new narrative corroborates the old.

We knew at the outset that anything in Night Vale is possible as long as it holds to strict continuity. Obviously things like time and reality are a bit shaky in our fictional world. A statement like “time doesn’t work in Night Vale” provides a lot of creative leniency, but we still need to make sure we use jumps in time in a way that feels deliberate, and not accidental.

I feel like I’ve written myself into plenty of corners in writing our show, but no more so than is normal in the writing process. Sometimes, I get near the end of a scene and realize what I think I’m getting at just won’t work (or it overlaps/contradicts something else), but that’s when re-reading old episodes comes in handy.

Also, outlines.

We make sure to thoroughly outline our episodes and novels so that we rarely encounter those issues. We need to know exactly how things are ending and how we’re getting there before we start writing.

Welcome to Night Vale has expanded from a podcast into books and of course, the international tour of live shows. Is your creative approach to each medium fundamentally the same or no? What is your favorite moment of creation in the Night Vale universe? Was there a specific episode or live show recently that was especially challenging to pull off?

Joseph: The working process is the same, in terms of the splitting of labor of writing and editing between Jeffrey and I. But we approach each medium on its own terms. A podcast, obviously, is all about what it sounds like. I perform the entire script out loud to myself a bunch of times to get a sense of the vocal rhythm of it, and if there’s a way to improve that. The live shows are also out loud, but more important, they’re in front of a large group of people. When writing them, you have to constantly be thinking of where the audience energy is, and where you want it to be going next. And then novels of course are a whole other beast. Tackling a story on that scale was fun but daunting.

Our current live show was an interesting one to write for us. We often start the writing of a live show by considering the challenge for ourselves and our performers that we want to work toward. The last live script was all about audience interaction, and the challenge there had been to build a full, emotionally fulfilling plot using the audience as the main character.

Since we had pushed the interactive element so far with the last show, we wanted to pull it way back for this one. We decided we wanted something that was: quiet, intimate, creepy, and sad. Then Jeffrey suggested he wanted to see how long our main performer Cecil could hold an audience while saying nothing at all.

And so we built a script that incorporates silences, longer and longer each time, until at the climax of the show is a silence that lasts for as long as Cecil can hold it. He’s held it for as long as 48 seconds during this tour, which is an eternity on a stage in front of over a thousand people, but not once in any of our performances of this script has any audience member disrupted the silence. As writers, building an emotional moment that consists of no words at all was a fascinating process.

What is the strangest/most unexpected fan letter or face-to-face interaction with a Night Vale fan that you’ve had?

Jeffrey: We were doing a live Night Vale show in North Carolina a couple years back, and a woman about my age (late 30s, early 40s) approached me and said “that’s my son.” She pointed to a teenage boy buying a poster at our merch table. “He’s autistic. He has a difficult time conversing and socializing. He rarely smiles or has casual conversations with us,” she said. But she told me he started listening to our podcast and it made him laugh, a lot. He started playing whole episodes for his parents in the car and in the living room. And they’d listen as a family. He would talk to them about the episodes, and it was the first thing they’d really been able to bond over. And she thanked me for helping to make a thing that brought them closer to their son.

I have never received a better or more touching compliment about anything I’ve written.

I loved hearing about the grassroots popularity of the show, your shock when the podcast became a cult hit, thanks in part to Tumblr. In hindsight, was it truly unexpected, or did you have some subconscious sense that you had created something magical before you ever showed it to anyone?

Joseph: I couldn’t have expected any of what happened. But I will say that when we started making Night Vale, it felt special to me. It definitely felt more whole and real and fully formed than anything I had managed to release before that. I remember saying to my girlfriend, “I think this could become something.” But I had no idea what that something would be.

Night Vale is now a brand under which—Night Vale Presents—you are both creating more serial podcasts. What is in the pipeline for this year and 2017? Do you foresee a time when you will close the Night Vale world to the public, once and for all, and do something completely different?

Jeffrey: I don’t foresee that time coming. But I also don’t foresee a lot of things. It’s not on our mind right now to shut down Night Vale, because we both really love doing it. Of course, the show would likely end at some point, because the history of all human life suggests Joseph and I will both die one day. But counterpoint: past performance is not a predictor of future results.

I’m always amused at the gusto with which interviewers ask me this question, yet here I am dying to know—will Night Vale be a film?

Joseph: We are always very careful about agreeing to do anything with Night Vale, because we are in the rare and lucky position of entirely owning and being the only people that work on the thing we make. So turning it into a book made sense to us, because we could write that book ourselves. And turning it into a live show worked, because we had the theater background to make that live show ourselves. But movies are a different thing. We’re not opposed to them. We’re just moving a lot slower, and learning a lot of things as we go.

Free association corner. Please answer with the first word that comes to mind (Both of you, of course).

Orson Welles

Joseph: Peas.

Jeffrey: Lena Horne

Cacti

Joseph: Water

Jeffrey: Baseball

Glow cloud

Joseph: Vanilla

Jeffrey: Leadership

Stephen King

Joseph: Maine

Jeffrey: Low Men in Yellow Coats

Stephen Colbert

Joseph: Oprah

Jeffrey: Amy Sedaris

David Lynch

Joseph: That gum I like.

Jeffrey: Owls

Cats

Joseph: Mixtape (the name of the cat I would have if my wife wasn’t deathly allergic to cats.)

Jeffrey: Jellicle

About Joseph Fink and Jeffrey Cranor

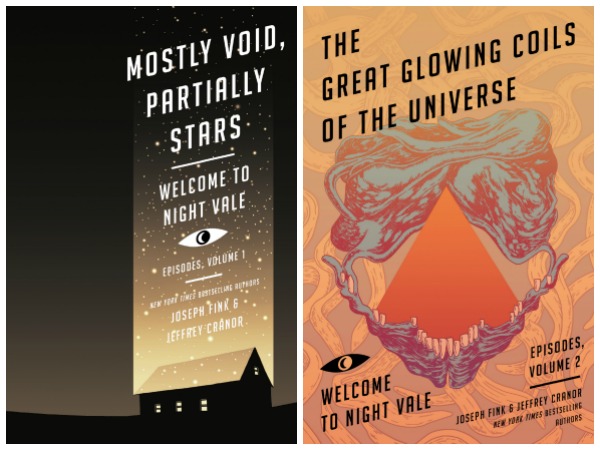

Joseph Fink and Jerry Cranor are the authors of WELCOME TO NIGHT VALE: A NOVEL and the script books for Season 1 and Season 2 of the Welcome to Night Vale podcast: Mostly Void, Partially Stars: Welcome to Night Vale Episodes, Volume 1 and The Great Glowing Coils of the Universe: Welcome to Night Vale Episodes, Volume 2.

Joseph Fink created and co-writes the Welcome to Night Vale podcast and touring live show. In his mid-twenties he started Commonplace Books, a very small publishing company, producing two collections of short works which he edited and laid out at his office job when his boss wasn’t looking. Later Jeffrey approached Joseph with the idea of writing a play about time travel. They co-wrote and performed the play What the Time Traveler Will Tell Us in the East Village in August of 2011. Soon afterwards, Joseph started brainstorming a new project he and Jeffrey could co-write and this led to the pilot episode of Welcome to Night Vale. He is from California but doesn’t live there anymore.

Jeffrey Cranor co-writes—along with Joseph Fink—the hit podcast and touring live show Welcome to Night Vale. He also makes theater and dance. He has written more than 100 short plays with the New York Neo-Futurists, co-wrote and co-performed a two-man show with Joseph, and collaborated with choreographer (also wife) Jillian Sweeney to create three full-length dance pieces: Imaginary Lines, This could be it, and Vulture-Wally. Jeffrey lives in New York State. For more on Welcome to Night Vale, visit: www.welcometonightvale.com.